PROscience : Сміючись і помру: Про життя і смерть видатних вікінгів

Про книгу

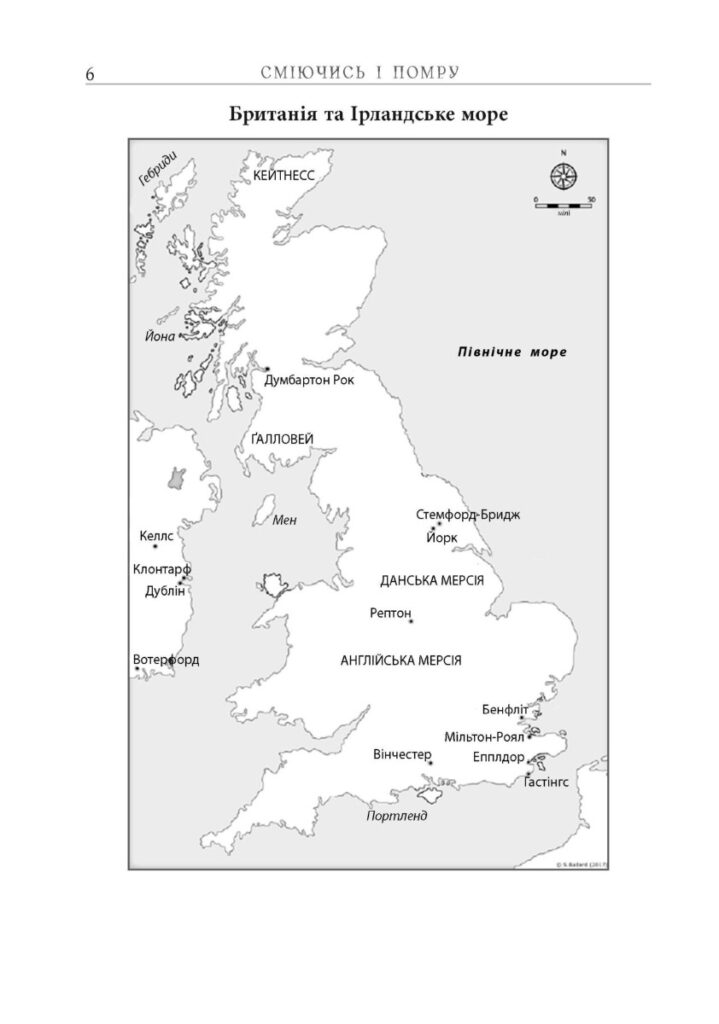

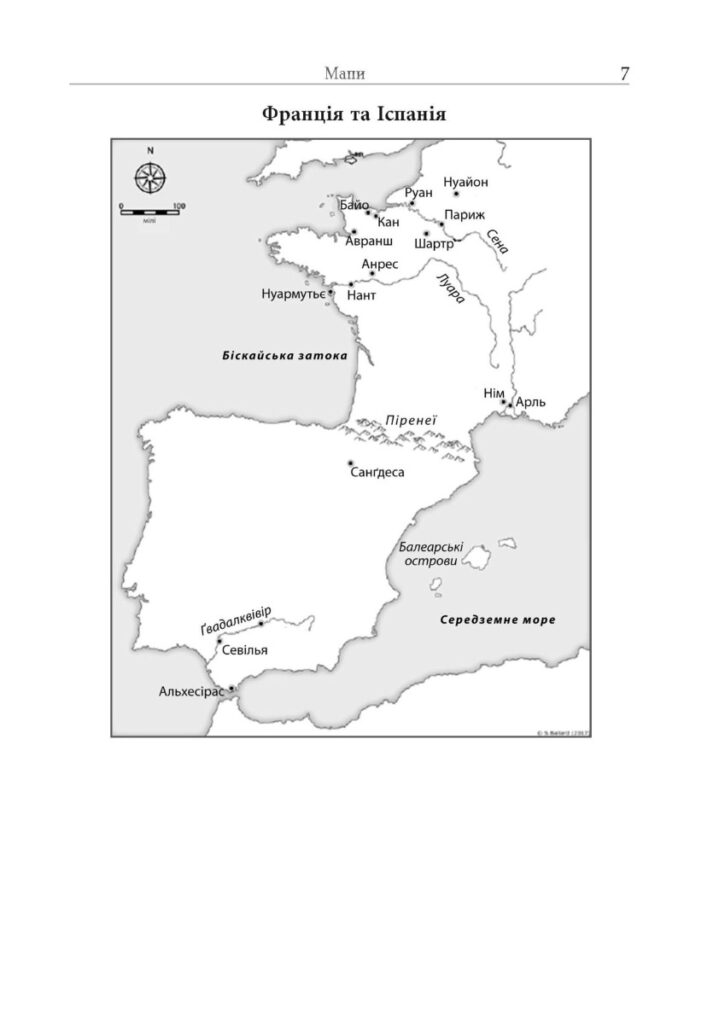

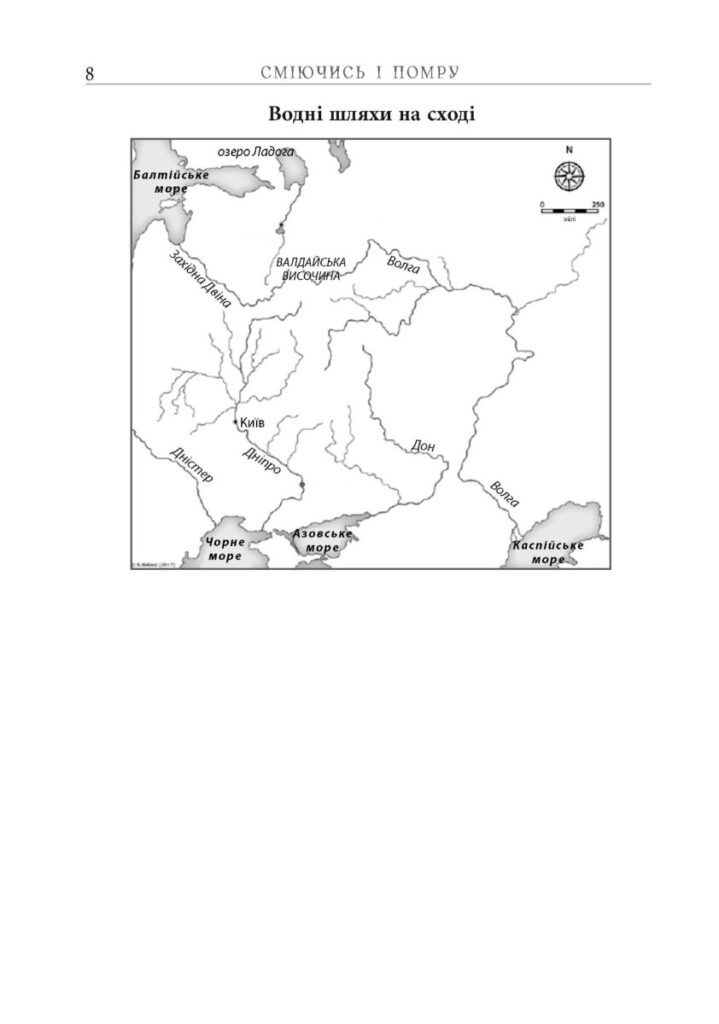

Вікінги були дивовижними воїнами, вправними мореплавцями, що завоювали світ і розчинились в історії, залишивши по собі чимало легенд і саг. От за останнє і взявся Том Шиппі, переконаний, що в давніх сагах Півночі набагато більше правди, ніж може здаватися на перший погляд. Ця книжка – наслідок ретельних порівнянь і зіставлень текстів саг із історичними джерелами. Автор відтворює знакові битви і походи, оживлює напівміфічних героїв і знаходить істину, приховану за метафорами давніх поетів.

Автори

Відгуки

Залишити відгук

Вже прочитали? Оцініть книгу від 1 до 5:

30 reviews for PROscience : Сміючись і помру: Про життя і смерть видатних вікінгів

Швидка покупка

Ваше замовлення вже у нас!

Найближчим часом наші менеджери опрацюють його та зв’яжуться з Вами для уточнення деталей. Дякуємо, що обрали Портал!

Очікую!

Joel Zartman –

Tom Shippey knows what he’s talking about, does it without pedantry, and even knows, in his deployment of the resources of language, when and how to use slang. If more scholarship were of the Shippey variety, our knowledge would be more accurate and achieved by more interesting means than it sometimes, unfortunately, is.In this book he again corrects the world. When this age passes, he will be held in very high regard.

Donna –

Takes highly motivated reader as it is difficult to keep straight multiple names for each individual that all look alike. But interesting take on the Vikings — A death cult in which even the GODS die in at the end times.

Philjones62 –

Started well and at times rather engaging. But I have no idea why the author felt it necessary to name drop Tolkien and link back to Game of Thrones through the book.Maybe it was just me but the sideways description of the myths got confusing as well.

Berni Phillips –

I was aware of Shippey by his reputation as a Tolkien scholar. I was not aware how readable he was for non-scholars. (He does say upfront that this book is aimed at more of a general audience.)This book is packed with much historical information but Shippey keeps it light and amusing at times with his asides and reference to pop culture. He refers to the Vikings TV show a number of times (mostly to point out where they get things wrong) as well as the classic Kirk Douglas movie and many other things. This book is fascinating, informative, and relatable.

Wesley Fiorentino –

Shippey’s book is a fantastic work of scholarship that is also an accessible read. The author effectively challenges the commonly held notion of the Viking Age as stretching from roughly 800-1066 or so and accurately notes that viking-like activity is recorded centuries earlier. Shippey also demonstrates that the ‘viking imaginary,’ or our popular notions of who vikings were and what they did, do not always square with the reality of their situations. What follows is a fascinating examination of the literary sources covering periods from roughly the fifth and sixth centuries all the way up to the eleventh century. The reader is treated to insightful and nuanced analyses of a plethora of sagas covering mythical/legendary figures like Sigurd and Sigmund, quasi-historic figures such as Ragnar Lothbrok, and well-documented figures such as Egill Skallagrimsson and Harald Hardrada.Shippey provides a detailed, thorough, and very persuasive examination of Icelandic sagas and similar source material. Through close reading of these stories Shippey identifies the values, customs, and mindset of the historical vikings. I think an idea put forward by the historian Robert Darnton is applicable here. Namely, that in order to understand the strange and alien customs and ideas of peoples far removed in history, we should single out the points that seem the most strange or mysterious and seek to better understand them. Shippey does an excellent job of this. In his case, this means trying to understand why vikings were so willing to risk their lives raiding, pillaging, and murdering. Why was it so admirable, as in Ragnar’s case, to laugh as one dies? Shippey attributes this to a particularly grim sense of humor, largely shared across the warrior societies of early medieval Scandinavia. This ‘Bad Sense of Humor,’ as Shippey terms it, is informed by the experiences of centuries of war, raiding, and death. Shippey charts examples of this sense of humor and the often tragic scenarios in which they appear in sagas and poetry dating across centuries and set in Scandinavia, Britain, Ireland, the Continent, and as far as Russia and Asia. It is a truly comprehensive study of the viking mindset as it is manifested in the surviving literature complete with Shippey’s original analysis and humor where appropriate. An excellent read for anyone interested in the historical vikings and their myths and legends, or in early medieval European history.

Julie Davis –

Shippey begins by explaining that in the Vikings’ own language, Old Norse, the word “viking” meant pirate or marauder. Most Scandinavians were not Vikings, though most Vikings were Scandinavians. Academics have been portraying Vikings as if they were just misunderstood Scandinavians.Academics have laboured to create a comfort-zone in which Vikings can be massaged into respectability. But the Vikings and the Viking mindset deserve respect and understanding in their own terms — while no one benefits from staying inside their comfort zone, not even academics. This book accordingly offers a guiding hand into a somewhat, but in the end not-so-very, alien world.Disturbing though it may be.I love Shippey’s understated humor. And also his premise.What’s really interesting is that, as you work your way through the book from prehistorical sagas to those which intersect with documented events, you find yourself absorbing the Viking culture. Rereading The Return of the King recently for a book club I found myself nodding at Eomer’s berserker-style fighting when he thinks all is lost. Fighting for the sheer fact that he may lose but he’s taking everyone with him. It resonated all the more because I knew Tolkien loved Norse mythology and had translated that sense to this scene. To befair, that’s why I began reading this book in the first place. I wanted to see where his writing showed echoes of his love of that culture. So – mission accomplished.It is definitely a scholarly book, albeit written in a very conversational style a lot of the time. Eventually I began skipping sections which talked about the differences between three versions of a saga and what proofs of historicity there were. There’s a lot of the book that is so readable that it’s easy to get a lot out of it even if you don’t care about the scholarly depths.

Charles Haywood –

In these days where man is held to be homo economicus, we are told that all people are basically the same, and what they want, most of all, is ease and comfort. Real Vikings prove this false. Instead, they reflect back to us a strange combination of very bad behavior and until-the-last-dog-dies virtue. Tom Shippey wants to talk about those real Vikings, not the sanitized ones who were supposedly much like us, just colder. If you read this book, therefore, you’ll get the Vikings in all their bloody, malicious glory.Shippey (a professor of Old and Middle English literature, and one of the world’s leading authorities on J. R. R. Tolkien) tells what we know about the Vikings, primarily from their own stories about themselves, the sagas. He combines this with other sources, including archaeology and the written histories of those with whom the Vikings came into contact, to create a vivid and compelling narrative. It may seem strange to treat the sagas as history, since fantasy elements, from dwarves to dragons to Valkyrie, are ubiquitous, and many were written down centuries after the events in them took place. The author takes the position, apparently not uncontroversial, that the sagas can nonetheless be used as history, though with caution and only in some instances. Either way, the sagas show the Viking mentality, not so much through the plots of the stories, but through the actions of the people in them. Most of all, it is this Viking mindset that Shippey cares about; he calls it “a kind of death cult,” which does not seem an exaggeration.Shippey is well-versed in the languages in which the sagas were written, including Old Norse; he does his own translations. Given the bowdlerization that is common in pre-modern translations, this is very helpful to the reader. The stories in the sagas are very complex, largely due to the tangled webs of kinship they portray. These are not fairy tales, with a simple story and simple moral, but Shippey does an excellent job of exposition. He emphasizes that sagas aren’t meant to be beautiful or delicate; they aim instead to follow extremely strict rules of rhyme and meter, and are full of complex grammar and obscure allusions. The creation of excellent poetry was regarded as a high virtue and accomplishment for men in their off hours, when they weren’t killing other men.Vikings are often incorrectly seen as synonymous with Scandinavians. In Old Norse, vikingr meant simply pirate or marauder. “It wasn’t an ethnic label, it was a job description.” Shippey rejects revisionist accounts that try to paint the Vikings as settlers, or traders, or nice people who just occasionally got caught up in fighting. Plenty of Scandinavians were settlers, traders, and nice people—just not the Vikings. For three hundred years, they stole and murdered across much of northern Europe, especially England, and got as far as Constantinople and southern Spain. “To the modern mind, it is amazing, almost incomprehensible, how so many thousands of men, over generations, took appalling risks in small boats and continuous hand-to-hand and face-to-face confrontations with edged weapons, for what do not seem to us to have been very great financial returns. Viking armies were often defeated, even exterminated, but there never seemed to be any difficulty recruiting another one.” What made this possible was the Viking mentality.Shippey’s book is both analysis and history. The history begins where Viking histories normally begin, with the sack of the monastery of Saint Cuthbert on Lindisfarne, in A.D. 793. It ends with Harold Godwinson’s defeat, in 1066 at Stamford Bridge, of the giant Norwegian king, Harold Hardrada (whose name Shippey translates, roughly, as “Hard-Line Harold”). The actual causes of the eruption of the Vikings are not completely clear, because there are almost no written records from Scandinavia of the time, but they probably have to do with upheaval and a power vacuum in Scandinavia. Intertwined with history, Shippey offers his careful and detailed parsing of sagas, combining that with evidence from archaeology. Much of this seems vaguely familiar to the reader, because Vikings have been staples of popular culture for two hundred years, but the more you read about real Vikings, the less familiar it seems (although a few works of modern fiction, such as Eric Rücker Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, do manage to capture a real Viking feel).As he moves through history, Shippey itemizes core features of the Viking mindset; then illustrates and expands on them. The single overriding feature was an absolute need to be brave. Cowardice was utterly disgraceful. Part of that was never giving in. Fighting to the last man was a baseline Viking expectation. We can understand that; it’s to some extent part of our own culture (or was, until we were pansified). Another feature, though, is harder for us to grasp—losing isn’t the same as being a loser. Vikings lost all the time; there was no disgrace in that, as long as you kept the right attitude, which was not giving in. If you had to give in physically, not giving in mentally would do. And the best way to show that was to die laughing (hence the title of the book). That laughter wasn’t ironic or self-referential, though. It was malicious.If you laughed as your enemies killed you, because you knew how they were going to die soon too and you’d get your vengeance, that was admirable. The goal wasn’t stoicism (which was often the goal of other martial societies, particularly the American Indians); it was getting one over on your enemies, and knowing it. Or if you bided your time as a defeated slave, forming a plan to kill and mutilate your enemies, then chuckled over their bodies, that was admirable too. (It is, as Shippey says, no coincidence that our word “gloat” comes from Old Norse.) Waiting to get back at your enemies so as to do it well is high-class behavior; it’s low-class thralls that lose their tempers and strike back hastily. And if you simply can’t get vengeance, you can make a dark joke, like the saga hero who, cut terribly across the face in hand-to-hand combat onboard a ship, grabs his gold, says “The Danish woman in Bornholm won’t think it so pleasant to kiss me now,” and jumps overboard to sink beneath the waves. Being humorously nasty is also admirable, like the man who, as he is about to be decapitated after a battle, asks for one of his enemies to hold his hair back so it doesn’t get bloody—then, as the axe falls, jerks backward so the helper’s hands are cut off, and dances around, laughing and shouting “Whose hands are in my hair?!”Being comfortable with losing continued even after death. Those warriors chosen for Valhalla were not promised eternal life or eternal happiness; they were promised a good time until Ragnarok, the final battle, whereupon all of them, and all the gods, were to lose and die permanently. In the Viking ethos, this makes sense, because you can only show that you will never give in if you can be defeated. The goal isn’t to avoid defeat, certainly not by switching sides to gain advantage. It’s to show your worth, come what may. Many have pointed out that the gods in the Iliad are, in a sense, lesser than men because their immortality makes everything they do ultimately trivial. Not so for Vikings, or their gods.Fighting was the number one Viking activity, of course. In all the sagas, there is a definite exaltation of strongly masculine behavior, mostly fighting but wine and women as well. Vikings had a general love of constant violence, including games intended to create violent disputes among friends out of nothing. They also invariably reacted with a hair trigger to insults; and when they lost their lives, as they expected to someday, if not laughing ideally offered dying last words that were not self-pitying but were laconic, such as “bear to Silkisif and our sons my greeting; I won’t be coming.” Self-control was extremely important—showing any weak-seeming emotion or offering any reaction (other than violence or laughter) was looked down on, even if severely injured or having lost a child or wife. Vikings didn’t cry, ever. All this behavior was, collectively, drengskapr, basically a code of honor, the function of which Shippey analogizes to later European dueling, which served important functions tied to the core male need for validation and hierarchy. Its opposite, naturally, was dishonorable behavior, such as killing the defenseless, cowardice, or breaking an oath; such actions meant either a loss of face or expulsion from the community.Despite the inherently masculine nature of drengskapr, women appear often in this book. Shippey notes that in the sagas women are “not themselves Vikings by trade, but often the most determined instigators and proponents of the heroic mindset.” The “sagas of Icelanders especially are full of dominating and aggressive women.” Numerous sagas turn on the actions of women, seeking revenge for slights or harms to them or their families, or rejecting an ambitious warrior until he achieves more fame. Old Norse even has a special verb just for women taunting men as cowards.Beyond the sagas, as with all the peoples descended from “Germanic” barbarians, women occupied significant roles in society. This is in sharp contrast to the East, where women were kept hidden and exercised influence purely behind the scenes. Women were out and about in Viking society (and in other Germanic societies, such as the Franks, causing scandal in Outremer among Muslims during the Crusades). They ran businesses, owned property, signed contracts, and generally acted with a great degree of independence. Vikings had no harems—although Vikings made a lot of money supplying young women to Muslim harems (and some high-status Viking men kept concubines). Slaves were the Vikings’ number one cash generator, and Muslims their number one market, since Christian Europe strongly disfavored slaves, even at this point, and Scandinavia itself didn’t have the money to buy a lot of slaves.In other words, contrary to the modern propagandistic myth, there’s no indication women as women were oppressed in Viking society (which is true for most, if not all, Western societies throughout history). As usual, relations between men and women were a constant negotiation where everyone was trying to muddle through together. In conflicts, women usually gave as good as they got, and exemplified similar courage as men. Voluntarily choosing to die, “[Brynhild] regards Sigurd as her real husband, her frumverr or ‘first man’; she means to go with him. Of course, she also had him murdered, but that does not affect her real feelings or her sense of what’s right.”Where women appear not a single time in this book, however, is as warriors, because Viking women warriors are a total myth. Last year widespread coverage was given to a claim that the grave of a Viking woman warrior had been uncovered. Fake news, which was quickly disproven, though that was not given any coverage at all in the popular media. Viking women warriors simply didn’t exist. “Viking warrior” is a tautology; “Viking woman” is an oxymoron. Neither history nor saga mentions women as warriors. What about the famous “shieldmaidens,” you ask? A thirteenth-century Danish historian, Saxo Grammaticus, created that legend out of whole cloth in imitation of myths about the Amazons. The sole mention in any actual saga of any woman warrior is in The Saga of Hervor and Heidrek, a thirteenth-century mashup of several earlier sagas, where part of the plot revolves around a woman, Hervor, who takes up arms after her father and brothers are killed (summoning her dead father, Angantyr, from his barrow grave to give her his sword, Tyrfing). (She was the inspiration for Tolkien’s Eowyn of Rohan, depicted, like Hervor, as golden haired in golden helmet.) This is all obviously just fantasy no different than that about dwarves and dragons. Such fantasies aren’t new; people have been projecting their fantasies onto Vikings for more than a thousand years. In the ninth century A.D. the Muslim ruler of Spain, Abd al Rahman II, sent an embassy to the Vikings, led by an ambassador, nicknamed al-Ghazal (“the gazelle,” for his good looks). It’s not clear precisely where he went or whom he met, because in what he wrote he was less interested in writing useful detail, and more in telling us that the custom of the Vikings was “no woman refused any man,” and that the queen of the Vikings was infatuated with him. Al-Ghazal’s writings show, as Shippey says, “we are deep in Male Fantasy Land,” and the same is true of Hervor. (Muslims, and the Byzantines, did interact quite a bit with the Vikings; more accurate than al-Ghazal was the record of the tenth-century Ahmad Ibd Fadlan’s mission to the Rus, which forms a large part of the backstory to the movie The Thirteenth Warrior and which Shippey discusses at length, mostly to show that the Vikings were fine with sex slavery, ritual murder, and gang rape.)Along similar lines, you often hear that the Valkyries were women warriors, a trope that shows up, for example, in modern movies based on the Marvel comic books. Shippey makes clear that they were nothing of the sort (addressing the question directly never comes up for him, any more than discussing whether the Vikings carried iPhones or used machine guns). The Valkyries were Odin’s servants, acting as harvesters, or rather recruiters, who picked which warriors would die in battle, and thus join Odin in the halls of Valhalla. They often picked the strongest men, who were brought low by seeming chance, but actually by the Valkyries or Odin himself—a way for the Vikings to explain the seeming randomness of death in battle. But the Valkyries weren’t warriors. At all. They were more like the Greek Fates, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos; and overlap with the Norns, the Norse rough equivalent of the Fates. Nor were they aspirational figures for women in Viking society.Silly claims about female Vikings are part of a larger problem with the corruption of everything by ideology—news, science, history. A claim that a Viking woman has been found is useful. It can be, and is, used to support idiot actions like allowing women into the military, and more generally to aid the ongoing massive propaganda campaign to pretend that not only are there no real differences between men and women, but that women can do anything that men can do, only better. (We have seen this on display in recent weeks in the blanket coverage given to the Women’s World Cup, an unimportant event that very few Americans care about, and the winning of which is equivalent to being the world’s tallest midget.) Thus, such a “discovery” is feted around the world and the “discoverer” briefly becomes an international celebrity, before returning to a promotion and permanent job security. A claim that a male Viking burial has been found is boring and gets the claimant nothing. Along similar lines, Shippey notes several attempts to feminize Viking history, such as when in 2014 the British Museum censored the translation of a runestone inscription to change phrases such as “They fared like bold men far for gold” to “They fared far for gold.” As Shippey says drily, the word men “is not favored academically.”Fortunately, this book is not marred by any such distortions. It’s an uncut presentation of Viking behavior, straight up, no chaser. After you read it, you’ll probably be glad you weren’t around when and where the Vikings were. Still, as you order some knickknack off Amazon to give you a brief rush of consumer enjoyment, briefly beating back your ennui, you’ll probably feel some tug toward the grandeur and glory of the Viking mindset, and wonder whether modern life, lacking any transcendence, is as hollow at its core as it seems.

Kari Janine –

This subject is of great interest to me, so I can’t bring myself to rate this lower. The obvious research and scholarship of the author also merit at least the average rating. I cannot go any higher. After reading many of the original sagas, I was hoping for more insight. This was essentially a retelling, in no discernible order. The narrative did not flow at all. I felt bounced around from story to story. Even worse, the chapters were peppered with “as I’ve told you before…”, and “more on this later.”I’d rather reread the sagas themselves.

Heideblume –

È così ricco di contenuti che non mi basterà una lettura per apprezzarne il valore.

Tim Renshaw –

Starts and ends strong for us not in the Norse history academic world. Starts and ends strong for us not in the Norse history academic world. The middle part got a little bit too technical and in depth on facts about which I didn’t care as much as the overall history. but for those actually in the field I’m sure the entire thing is very riveting.

Michael –

A good overview of the Eddas and the Sagas. Much of Shippey’s premise that the Vikings excelled during the Viking Age was due to their world-view is something I’ve taken as truth for so long that his argument seemed superfluous to me. Other readers will undoubtedly think otherwise.

Scott –

Shippey is well known for his Tolkien and Anglo-Saxon scholarship, and he brings that history and philology into this survey of Viking customs and literature. It’s a very fun read which manages to have depth and an affable readability at once.

Jason Bray –

This book was an excellent and interesting read in many parts. The stories of the Vikings are unfailingly entertaining and the author’s focus on the way that the Viking mindset differs from ours is very compelling.On the other hand, this is a challenging book for the uninitiated. I do not personally know much about the various sagas, so much of the discussion about sourcing is “inside baseball”. It can be challenging to even hold the thread of what is happening when “the central figure.. is Gunnar, his father is Gjulki, his sister is Gundrun, and he has brothers… Giselhar, Gunthorm or Guttorm.”I suspect if you were already very familiar with the Viking sagas, some of the detailed analyses of sourcing would be of great value. But what is left is still very compelling. As a likely descendent of Vikings myself, I find it almost uncanny how deeply I resonate with some of their descriptions of what is honorable of virtuous behavior. It arouses a curiosity in me of whether there is some familial connection, or whether it is so deeply imbedded into my cultural heritage that I can “flash-back” to sympathy for their point of view without consciously agreeing with it.Anyway, it’s not easy or light reading, but if you like to understand how differently historical people might think than we do, it is a deeply thought-provoking read.

Anna Mussmann –

Whenever I picked this title up I would tell my husband, “I’m reading that book about sociopathic Vikings again.” Shippey’s portrayal of Viking culture and mentality might actually be useful as a cure for racism. Anyone who has swallowed the idea that white people were inherently superior to the “primitive” folks they conquered throughout history will find this book a rude awakening. It’s a reminder that pagan warrior cultures tend to be pretty dysfunctional, violent, and nasty (from a modern, Christian-influenced perspective) no matter where they come from.Shippey’s thesis is ostensibly focused on the Viking fascination with heroic death, but in actuality he allows himself to range more widely. His focus is on learning about Vikings through the sagas and poetry they and their descendants left behind. This approach puts him at odds with most historians, who consider literary evidence less reliable than he does. Shippey frequently snipes at professional historians. He does so in a witty and endearing way that quite won my heart. Despite my good will, though, I’m going to take a break from the book at the halfway point. It’s long and a bit technical in places, and I’m ready to hold off on violent pagans for a while no matter how sardonically humorous and poetical they were. 3.5 stars.

Paul Henry –

I found Laughing to be informative, since my knowledge of the early middle ages is/was very sketchy; it’s well written, well researched. My problem with the book is the sheer amount of detail that bogged me down as I read it. Another problem I had was the names, old Norse names I’m completely unfamiliar with, several Olafs, at one point Harold and Harald were fighting a battle in England as I remember. Very difficult to follow, keeping who’s who. Unless you really want to up your knowledge of this time period, I’d look for a lighter read.

Liam –

Scholarly, but not restrictive to scholars. Shippey does a fantastic job of making the topic interesting and informative. Shippey is a philologist, and you can tell, but he doesn’t knock archaeology. He does a great job making this easy enough to read.

Ned Ludd –

4.5 ⭐️

D –

In Laughing Shall I Die Tom Shippey takes a serious look at the Icelandic sagas and attempts to ask what we can learn from them about the Vikings. Using this premise he retells the great Viking sagas as well as the history of Viking raids and conquests while at the same time establishing a very convincing outline of the viking world view, so different from ours. I learned a lot from this book both about history, pagan culture as well as skill of the historian. The way Shippey shows you how to read deeper into the sagas looking for implied facts or thinking frameworks is both convincing and instructive. I really enjoyed this very unusual book I only wish I had someone to recommend it to.

Gregory Amato –

Passion for the subject, clarity in explaining its complexities, and often a bit of humor make Shippey’s work so readable. Here the dense and difficult are accessible, often accompanied by the cultural references more readers will be familiar with. So you haven’t read Gongu-Hrolf’s Saga, but you have seen Vikings? That’s not a problem, there are plenty of fantasy elements with a hint at a real person in both. Shippey’s description between the popular culture references (Vikings, Game of Thrones, Lord of the Rings) are both relevant and welcome as markers most readers will recognize.But even if it were dense and difficult in style, this book would still be worth reading for the insights. Norse sagas are notoriously difficult to understand, both in terms of the conversations they describe and the actions people take. What were the values these people had? Sagas almost never discuss emotion or thought process. Internal dialog is anathema to those stories. Shippey takes his knowledge of the language, culture, and history, and contextualizes many of the most difficult scenes. As well as he can, and he’s very clear on the limitations, this a series of case studies on viking psychology.If you’ve read the sagas already, this book is a great companion. If you haven’t you still get a great introduction to some of the most famous Old Norse characters.*Shippey also coauthored a three-book series about vikings (The Hammer and the Cross) with Harry Harrison under the pseudonym John Holm. Highly recommended if you like alternate history or Norse mythology.

Truls Ljungström –

Detta är en mycket irriterad historikers populärvetenskapliga sammanfattning av varför alla som vill skapa politiskt korrekta vikingar gör bättre i att dra något gammalt över sig. Han har rätt. Det hindrar inte att bokens relevanta del är de första 20 sidorna, medan resten framförallt syftar till att underbygga tesen med så mycket fakta att författaren blir svårare att avfärda. Det borde inte behövas för en professor emeritus med vikingar och folkvandringstid (och Tolkien) som fokus, men gör det tydligen. Det förefaller som om vissa saker förblir konstanta. Behovet av att mota bort popideologier som vill vara vetenskap inkluderade. Shippey gör en poäng av att därför gå igenom de grövre delarna av vikingarnas traditioner, såsom skeppsbränningarna med de däri avrättade slavinnorna, eller listerna använda mot bosättare på kusterna. Målet är att göra det omöjligt att inte ta med Vikingatraditionernas psykologiska aspekter i beskrivandet av dem. Återigen något som borde vara självklart men inte är det – tydligen. Om man kan sin historia är denna bok rolig, men inte värdefull. Om man är drabbad av amerikanism, eller av annan anledning inte var uppmärksam när järnåldern gicks igenom i skolan, är det mycket värdefull, för att inte säga ordinerad, läsning. Å andra sidan är bokens formgivning sådan att den snarare tillhör de redan frälsta än de som skulle behöva dess information.

Themagicofworlds_be –

– The Magic of Wor(l)ds (https://themagicofworlds.wordpress.com/) blog is een hobby, recensies en andere boekgerelateerde berichten worden gratis geplaatst.Ik ben dankbaar voor het ontvangen van een gratis boekexemplaar van de auteur/de uitgeverij in ruil voor mijn eerlijke mening. -Na het lezen van ‘Lachend naar Walhalla’ moet ik niet alleen mijn brein even tot rust laten komen, maar heb ik ook een mooie lijst van boeken en films die ik wil lezen en kijken.Het boek met zijn voetnoten is een goed voorbeeld van ‘going down the rabbit hole’, want het is dankzij Tom Shippey heel makkelijk om je te verliezen in de geschiedenis van de Vikingen.Heel toegankelijk, moet ik zeker toegeven, vertelt hij aan de hand van saga’s en legendes hoe we eigenlijk deze periode en de mensen echt moeten zien / interpreteren.Het is een mooie, heel uitgebreide tocht doorheen de eeuwen en op het einde had ik echt het gevoel dat ik de waarden, de gebruiken en in het algemeen het ‘verhaal’ van de Vikingen beter begreep.Ze waren meer dan de woeste barbaren uit films, strips, series,…, ze waren namelijk mensen van hun tijd en hoewel dat voor ons vreemd overkomt, was het logisch toen en dat maakte deze auteur zeker duidelijk aan de hand van vele voorbeelden uit de literatuur.Maar is het allemaal waar of ook deels fantasie, want deze ‘bronnen’ / schrijvers leefden vaak veel later dan de gebeurtenissen die ze beschrijven?Dat blijft vaak de eeuwige discussie, ook hier in het boek, maar dat zet dan weer aan tot verder onderzoek, wat zeker geen probleem vormt met de bibliografie aan het einde.Een aanrader voor iedereen die interesse heeft in het Vikingen-tijdperk of de vroege Middeleeuwen in Europa.The Magic of Wor(l)ds

Takumo-N –

Really good, readable account of the viking mindset and dark but somewhat childish sense of humor (basically every hero in the Sagas is in an epic, mythological dick measuring contest). The author, at the beginning, goes through some Sagas to set the attitudes of Scandinavians of that era, then he goes on a more historical explanation of what those writings (poems, written and oral stories) could mean, and if anything of the sort happened, or could’ve happened. From interpretations of poems and stories, archeological findings, and other historian books Tom Shippey lays the reasons of why those Scandinavians travel so far for so long, with good to disastrous results, and it’s a pretty compelling argument.

Bones Green –

Ґрунтовний аналіз історії та світогляду вікінгів, саг Півночі й відповідних історичних документів. Зображення давнього світу суворих, жорстоких, поетично обдарованих і відданих складним уявленням про честь, гідність і гумор. Не залишить байдужими та може допомогти стати міцнішими.

Pam Shelton-Anderson –

I knew of the Sagas, primarily from Anglo-Saxon/Viking history, but had no idea how extensive these were. It was at its best when it paralleled historical sources. I liked that it covered the Vikings in eastern Europe/Russia, Scandinavia as well as the UK. I enjoyed the stories that seemed to be more pure myth/legends, though I often struggled to keep a lot of it straight. I have to give kudos to an author that can put a Monty Python reference in a book about Viking lore.

Barb Middleton –

I just wrote a long review when the app stopped and I lost it. Argh. The author uses many disciplines to show how the Viking hero is defined by defeat facing situations fearlessly, self-controlled and with wit. Everyone must die one day and defeat is motivation rather than discouragement. The use of Icelandic sagas, references to Tolkien, The Vikings tv series and more made this an interesting read.

Peter Krevenets –

Як же я міг встояти перед книгою із такою назвою? У ній стільки героїки, несподіванки та загадки! Урешті решт давно вже мені пора було прочитати щось про епоху вікінгів, про нордичні міфи та Сігурда. Вважаю, що обрав дуже правильну книгу, адже нарешті я дізнався, чи була правда у серіалі “Вікінги” та фільми “Тринадцятий воїн”, що там із засновниками Києва, чи дійсно вікінги тримали у страху всю Європу, а також важливіші речі – що норвезькі воїни любили поезію і часто самі складали вірші та що люди з кінематографічною біографією справді існують – це я про тебе, Гаральд Хардрада.

Sonstepaul –

An interesting way to tell about Viking culture and society through selected stories and themes. Shippey, and eminent scholar in several disciplines, uses key vignettes or figures from the sagas to try to make us understand just how the Vikings may have thought, how different from us. There is a sense of pushing back against modern desires to soften the Northmen, with many references to popular culture (such as the Vikings TV show and Tolkien, on whom Shippey is THE expert). Also a fair amount of head-shaking at modern tendencies.Not an entry-level read, but certainly enjoyable to those with a background knowledge.

Kottigel –

Це однозначно НЕ історична праця, тому якщо ви хочете почитати щось про історію скандинавів і вікінгів, шукайте далі. Це спроба розглянути менталітет вікінгів через призму огляду на героїв саг і порівняння їх з реальними історичними фігурами. І це літературознавча розвідка набагато більше, ніж історична.Загалом було цікаво, але 2 бали знімаю за фактологічні помилки (на які, до речі, вказує перекладачка) і за те, що автор ототожнює Київську Русь з Росією у відповідному розділі.

Daniel V. N. –

Shippey’s exploration of the viking era is in most cases a wonderfully approachable work of scholarly research. Shippey mixes the deep research with, at times, very plain and ordinary terminology, that one might not have expected to stumble upon.Shippey does a wonderful job at nuancing the many different narratives of the viking sagas, and at times that feels like a multi-verse conundrum to keep each version straight as a reader, meaning that I had to go back a paragraph sometimes to understand which saga Shippey referred to when a specific version of an event happened. I cannot imagine how it could have been done better, while still emphasizing that one of the big problems of describing the events of the Viking era is finding the common thread throughout the sagas and seeing what they agree on, and what they disagree on.Shippey does a terrific job at referencing the Vikings (2013-2020), and highlighting where the production company took inspiration, and what changes were made. As a fan of the tv series, I had naturally hoped that Ragnar and his family would play a bigger role in Laughing Shall I Die, but I trust Shippey’s expertise that Ragnar html5-dom-document-internal-entity1-amp-end Sons were not the be-all and end-all of viking history and myth.Examples of Shippey’s humour, and other weird sentences that Shippey got approved by his editors and printed:

assisted (in Hrólfs saga) by the advice of a one-eyed farmer whom anyone but an idiot would recognize as the god Odin in disguise.

However, the original and correct name for the founder of the dynasty may have been censored out by later Christian writers, for in Old Norse völsi is a word for ‘horse penis’.

Noting the accounts that say that he was struck down by disease, once specified as dysentery, she adds the speculation that the unfortunate effects of dysentery – unstoppably loose bowels – may have been the cause of his nickname. This is a theory one has to reject! If Ragnar had been famous for fouling his trousers, one can be sure that his loyal comrades, filled with Bad Sense of Humour, would not have called him anything as polite as loðbrók, or ‘hairy-breeches’. They would have come out with something much ruder, perhaps dritbrók, which I forbear to translate.

What did Scandinavia have to sell? It was suggested above that fur was the cocaine of the Viking Age, but perhaps – black fox-skins apart – furs were more like marijuana: bulk trade, steady demand. It was slaves, and especially slave girls and boys to fill harems and provide the harems with eunuchs, that were more like cocaine.

There are unfortunately a few areas where I find the language lacking, and while I might be in the wrong here, I think it would have benefitted Shippey and his publisher to have some of the specific mentions of Danish languages checked by someone who speaks, and writes, Danish:The first thing one can say about drengr is that it has become the normal modern Danish word for ‘boy’, en lille dræng, ‘a little boy’. While it is tempting to use as much ÆØÅ when presented with the opportunity, “boy” in Danish is simply “dreng”, not “dræng”.Beorn (an English name, but again almost identical with the Danish Bjorn) I think Shippey means “Bjørn”, here we prefer the usage of the Dano-Norwegian alphabet specials.Shuldreden hi ilc oþer and lowen.Wolden hi namore to putting gange,But seyde ‘We dwellen her to longe!’‘They shouldered each other and laughed,they gave up on the putting, they said, “We’re wasting our time here!”’ It seems to be, as a native Danish speaker, that the last line should say: “But said, ‘We dwelled here too long!” which does not change the meaning in any significant way, but therefore I would argue that the more direct translation should be preferable.My vuggestuen concern here, is that Shippey has quote clearly made mistakes that I only noticed as a native Danish speaker, so what other mistakes might be found by experts in other fields?

Elentarri –

This book is not for the squeamish! This is also not a straight-forward, narrative history of the Vikings, nor a treatise of Norse mythology. Shippey examines the lives, and especially the deaths, of the great heroines and heroes of the Viking Age, as is revealed in their own words – the Old Norse poems and sagas – as well as the words of others – various chronicles and accounts in other languages. This book is a fascinating and interesting look at viking psychology – what made the Vikings so different and so distinctive – as revealed by the literature (sagas, legends and stories) left behind by themselves and their descendants. The book progresses in a more or less chronological order, from the prehistorical sagas to those that correspond with documented, historical events. Shippey also makes some effort to explain how plausible the events described in the literature, as determined from archaeological findings, other historical texts and sometimes medical cases. While most vikings were Scandinavian, the majority of Scandinavians were decidedly not Vikings. The author also takes great pains to point out that “viking” is a job description, one that involves rape, murder, war, piracy, plunder, extortion, slaving, and occasionally trade (have to make money off the extorted and stolen goods somehow!). “‘Egil’s Saga’ is not a feel-good story. It backs up the argument that Viking society had a ‘psychopathic’ element in it. Or in their view, troll genetics.” from pg 116 of Laughing Shall I Die by Tom Shippey.I love Tom Shippey’s writing style – academic but also accessible, with a pithy and understated humour. I found this book examining Viking culture to be interesting, especially in terms of raising awareness of things I had never even considered, and wonderfully entertaining to read. I do suggest being at least vaguely familiar with Viking history before reading this book as it isn’t meant as an introductory text to the subject. Also, knowledge of some of the sagas (or at least that such things exist) would be useful, but isn’t particularly necessary to enjoy this book.Note: This is a book I will definitely re-read when I take up my (neglected) Icelandic Saga binge read one day.